Animation

Season 7 Episode 4 | 28m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Uncover Disney’s LA roots and how the city became the birthplace of modern animation.

Uncover Disney’s roots and Walt Disney’s first home as Nathan explores how Los Angeles became the birthplace of modern animation. Animators Jane Baer and Floyd Norman, producer Don Hahn, composer John Debney and voice actor Bill Farmer explain how the city transformed cartoons into the art form of animation.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Lost LA is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal

Animation

Season 7 Episode 4 | 28m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Uncover Disney’s roots and Walt Disney’s first home as Nathan explores how Los Angeles became the birthplace of modern animation. Animators Jane Baer and Floyd Norman, producer Don Hahn, composer John Debney and voice actor Bill Farmer explain how the city transformed cartoons into the art form of animation.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Lost LA

Lost LA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipNathan Masters: Long before L.A. inked its place in animation history, New York sketched the first scenes.

As late as 1923, The Big Apple still ruled the cartoon business-- home to stars like Koko the Clown and Felix the Cat.

But that August, change rolled in on a train from Kansas City.

With just some drawing tools and a sample reel in his suitcase, 21-year-old Walt Disney set up shop in the garage behind his Uncle Robert's house in Los Feliz, setting L.A.'s animation story into motion.

[Theme music playing] Announcer: This program was made possible in part by a grant from Anne Ray Foundation, a Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropy, and the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs.

Masters: This craftsman house on Kingswell Avenue was Walt Disney's first Los Angeles home.

Masters: Nice to meet you.

Man: Nice to meet you, too.

Masters: Thanks for having me.

Man: Yeah.

Welcome.

Masters, voice-over: Disney's great-grandson, Nick Runeare, took me on a tour of this historic landmark, lovingly restored by his family and saved from the wrecking ball.

Runeare: This is where the Walt Disney Company started, really.

Runeare: Yeah.

Let me show you the kitchen over here.

Just wanted to keep everything as original as it could be to-- to the time.

Masters: So, there it is.

There's the garage.

Runeare: Yep.

Masters, voice-over: This unassuming garage, a faithful replica of the original, marks the starting point of Walt Disney's entertainment empire.

With a battered film camera and an animation stand cobbled together from spare lumber, Walt launched L.A.'s first animation studio right here in his uncle's backyard.

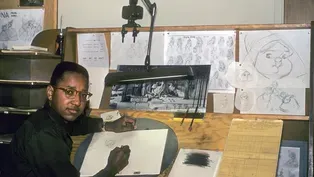

Waiting for me inside the house was legendary animator Floyd Norman, who got his start in the business working for Walt Disney in 1956.

Masters: This is such an amazing place and an important place in the history of The Walt Disney Company and animation, but it's really flown under the radar.

Norman: It really has.

Masters: Yeah.

Norman: As a matter of fact, I thought this home had been torn down decades ago.

Masters: Obliterated like so much else in L.A. history.

Norman: That's what we do with-- with L.A. history.

We bulldoze it down.

Masters: Sadly, sadly.

So what was it like to work for Walt Disney?

Norman: It was a kid's dream come true.

When I was a kid growing up in Santa Barbara, I learned about motion pictures in my junior high school library.

I learned about animated films in particular, but I did learn one thing.

I knew that one day, I wanted to go to Hollywood and make movies.

I wanted to go to The Walt Disney Studio and work for Walt Disney.

Masters: Yeah.

Norman: And guess what happened?

I got a chance to do all of that.

Masters: Wow.

You got your dream job.

Norman: I did.

I truly got my-- my--I did not want to go home at the end of the day.

After I had been at the Disney studio for 10 years, Walt Disney decided that I was not an animator, but that I belonged in his Story Department.

And that's how I ended up working on "The Jungle Book."

And think of what a lucky kid I was back in 1966 to have had the privilege of working with Walt Disney-- Masters: Yeah.

Norman: on his last film.

Masters: Last film.

So, when the average person hears the word or the job title "animator," they might think somebody with a pencil drawing a cartoon character, but there's really a lot more to it than that.

Norman: Mainly, we tell stories visually.

Keep in mind, the animator is an actor with a pencil.

Masters: Ahh... Norman: And they put that performance basically on a sheet of paper.

Norman: You also worked for another storied animation outfit.

Norman: I left Disney around the early seventies, and I was offered a job at Hanna-Barbera.

Totally different from Disney.

I remember the first show I worked on was "Josie and the Pussycats."

And then after "Josie," we did a reboot of "The Flintstones."

We thought we'd have all this material to pull from, but it turns out that Hanna-Barbera had thrown away all that early stuff they had done in the 1960s.

It had gone into the dumpster-- Masters: Oh, wow.

Norman: which meant we had to re-create "The Flintstones" from scratch.

Masters: Do you remember your first experience with animation?

Norman: My first experience was probably in middle school, and I decided to make my own animated cartoon.

And back in those days, you had to make all the art material yourself.

You couldn't go out and buy it.

So I had to get sheets of plastic and cut it up and punch holes in them and basically create my own production process.

I was shooting 16 millimeter Kodachrome, and I remember how glorious that film looked.

Masters: When you were just telling me about how you had to scrounge for materials and make your own set-up, that reminds me of what happened in this garage over here.

Walt Disney had to build his own camera rig, right, to-- to create his animation camera.

Norman: Yeah, that's what Walt and his brother Roy had to do.

Masters: Yeah.

Norman: You know, they had to basically build their own studio, starting from scratch, starting in that garage.

Masters, voice-over: I asked Floyd if he could teach me some basic sketching in the place where L.A. animation was born.

Norman: This is a cartoon version of you.

Masters: This is like magic.

That took you less than 30 seconds!

I mean, is there anything that you can just guide me through drawing?

Norman: Draw a circle.

Masters: Draw a circle.

OK. Norman: This is gonna be the body.

Masters: OK. Norman: Let's give him some eyes.

Masters: OK. Oh, big ones.

There we go!

Ha ha ha!

Norman: Ta-da!

[Blink blink] All right, folks.

As Porky Pig would say, "T-t-t-that's all folks."

["Looney Tunes" theme playing] Masters, voice-over: Walt quickly outgrew his uncle's garage.

Teaming up with his brother Roy, he moved into a storefront down the street, and by 1926, they upgraded again to a lot on Hyperion Avenue.

It was here, now the site of a Gelson's supermarket, where Disney and a cadre of talented cartoonists from Kansas City had their first breakthrough.

Oswald the Lucky Rabbit was charming, mischievous, and a hit with moviegoers as well as with the series distributor, Universal Pictures.

But before Walt could fully enjoy his success, Universal took control of Oswald, sending Disney back to the drawing board.

On November 18, 1928, Mickey Mouse made his debut in "Steamboat Willie," delighting audiences with fully synchronized sound.

[Whistles tooting] It marked the dawn of a new era in animation, with Disney leading the way, but competition wasn't far behind.

As Max Fleischer in New York introduced Betty Boop in 1930, in Los Angeles, many of the cartoonists who had followed Walt from Kansas City to L.A. started branching out.

Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising helped producer Leon Schlesinger launch "Looney Tunes."

Walt's old friend Ub Iwerks, meanwhile, created Flip the Frog for MGM.

Walt knew that staying ahead meant his animators needed more than just technical skills.

They needed a foundation in the fine arts.

So he teamed up with Nelbert Chouinard, founder of the Chouinard Art Institute, which later became CalArts.

To learn more, I headed up to Santa Clarita to chat with animation historian and CalArts professor Mindy Johnson.

Masters: I've heard this line from Walt Disney from some interview that he did.

"It all started with a mouse."

Johnson: Oh, there was so much long before the mouse, and there were many other mice before the one mouse we're talking about.

Masters: So, 1929, Disney is no longer producing the "Oswald" series.

Johnson: Mm-hmm.

Masters: And around this time, Disney meets up with Chouinard.

Johnson: Walt realizes, "My artists need to up their game a little bit"... Masters: Ahh... Johnson: because they wanted to experiment with human forms, and Walt's got a longer vision for animation at this point.

Masters: They're not just making moving cartoon strips anymore.

Johnson: No, no.

Masters: They're elevating their game.

Johnson: Yeah, absolutely.

Walt realizes it's through the artistry.

So, Walt goes to all the different art schools in town-- Otis and UCLA and all the different campuses.

And he's pretty much laughed out of everybody's offices because "We're artists.

We're fine artists.

You're doing comics.

That's--" Masters: They didn't take his work seriously.

Johnson: No, no, you know, until he got to Chouinard Art Institute, met with Nelbert Chouinard.

And she said, "I know what you're doing here.

I've been following your work, and I think you have an opportunity to build a real American art form.

You bring me your artists.

We'll work out the tuition.

You bring them, and I'll train your animators to be better artists."

And that began probably one of the most long-term foundational alliances within animation history.

Masters: Between Chouinard, Nelbert Chouinard and Walt Disney.

Johnson: Yes.

Absolutely.

She--in fact, Walt would pack his artists up in his car.

He'd drive them down once a week.

Masters: He drove them himself-- Johnson: Yes, he did.

Masters: in his own car.

Johnson: Drove them down to the Chouinard Art Institute.

Masters: Wow.

Johnson: It was still at that point, you know, comic gags, sight gags, rubber hose-y characters, but their human forms and other characters start to develop.

For any artist to be exposed to other art forms and to see and experience things in other ways, helps to sort of expand their own artistry and their own view on things.

They were teaching in this very progressive style that Nelbert had helped cultivate and develop.

Masters: I can imagine people across the animation industry, they were working in a sort of artistic echo chamber.

Right?

Johnson: Exactly.

Masters: ...to each other's work.

Johnson: Very isolated.

Masters: And when Disney brought them to Chouinard, it was, you know-- Johnson: Yeah, it's a bigger world, right?

Masters: Yeah.

Johnson: And that reflected back in the quality of work being produced at the studio.

Film announcer: Remember as a kid how you made your own movies by drawing little figures on the pages of a pad and flipping the pages to make the figures move?

That's the basic principle behind animated pictures today, but that's not all there is to it.

Masters, voice-over: Traditional animation was labor-intensive, to say the least.

For every second that audiences saw, the animation camera captured 24 separate images--drawn, inked, and colored by hand on celluloid sheets.

Much of that work happened in Disney's Ink & Paint Department, where a team of artists, mostly women, turned rough sketches into camera-ready cels, adding definition and color.

While most studios phased out this department with the rise of computer animation, Disney Animation Studios in Burbank still embraces the tradition.

I caught up with the current team of four--Charles Landholm, Dave S. Smith, Annie Hobbs, and Antonio Pelayo-- Working in a space that used to be home to hundreds of artists.

Film announcer: Here, hundreds of pretty girls in a comfortable building all their own color the drawings with sheets of transparent celluloid.

Masters: Inking is just sort of like a fancy name for drawing, or is it a lot more complicated?

Pelayo: It's a lot more complicated than that.

With inking, you're literally putting the ink pen down, and then once you start the line, you don't stop.

Masters: It's one stroke.

Pelayo: One stroke.

Masters: So, what are we looking at here?

Pelayo: This is the animator's pencil drawing.

Masters: OK. Pelayo: It goes to the inker.

And the inker's job is to transfer those lines onto a cel.

Would you like to try it?

Masters: I mean, sure.

That's your tool.

What you're gonna do, you're gonna put that stick right there.

Masters: OK. Pelayo: And then get in there.

Masters: Get in there.

Oh, my goodness.

OK. OK. Ha ha ha!

Pelayo: You got the ink flowing.

Masters: This is why this is your job and not mine.

Ha ha ha!

Pelayo: It's, you know, doing the line, then you got to clean it.

Do a line, got to clean it.

Masters: Yeah.

Yeah.

If we end up with something that looks--that approximates Mickey Mouse, I think I'll be happy.

[Laughing] Film announcer: Now the picture moves into its final stage: color.

In the studio paint laboratory, all colors used are made up from secret formulas.

Masters: Disney, I mean, not only invented its own colors, but it actually produced the paint right here in the Ink & Paint buildings.

Landholm: Yes.

In fact, on this side of the wall here is all of our Disney palette.

The Disney palette has fun names like Cornflower, Cafe, Cherry-- Masters: I noticed Mickey's pants are Lobster.

Landholm: Yes, this is Lobster.

It's very bright red.

Lobster 17, actually.

Masters: You can just look at these two chips, and this almost says "Mickey Mouse" to you.

Landholm: Definitely.

Masters: And because these colors are so distinctive, it's not just red and not just yellow.

Landholm: No, it's Marigold and Lobster.

Masters: Right.

Yes.

Ha ha!

Film announcer: The inked celluloids next go to the Painting Department, where more pretty girls apply the final colors on the back.

Hobbs: This is what a final inked cel would be like.

And if you want to run your fingers over the top, you can feel that it is--it's on top of the cel, right?

Masters: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Hobbs: It doesn't sink into it like a paint.

Masters: Right.

Hobbs: And our next step is, we want to apply the color.

We do not want to apply the color on top of our ink lines.

Masters: Ooh.

Hobbs: We actually flip it the other way.

Right?

So, we're going to paint on the back side of the cel.

Masters: Oh!

Hobbs: So, we're gonna flip it over.

Would you like to try?

Masters: I'll give it a shot.

Hobbs: OK. Masters: Ha ha!

Now, because Disney has these proprietary colors like Lobster and Marigold, that must mean that Disney animation looks unlike any other company's animation.

Hobbs: Correct.

We did have our own color palette, and that was because Walt literally just didn't want to kill people with color.

Right?

It was a new thing, a new genre of storytelling.

The color success story is "Flowers and Trees."

And they actually did two versions of that short.

They did a black-and-white version just to make sure everything was good.

Ha ha!

Masters: Yeah.

Hobbs: And then they--they redid the entire thing in color, and it worked.

Masters: Oh, wow.

Hobbs: And that was the big color success for the Disney company.

Here's how he turns out at the end.

Masters: Oh, wow.

Masters, voice-over: From Ink & Paint, I made my way to the final resting place of Disney's animation artwork-- a secure, climate-controlled archive once known as "The Morgue," now called the Animation Research Library.

Fox Carney showed me inside.

Carney: Come on in here, Nathan.

We have some original artwork that we'd love to show you.

Masters: This is stuff the public doesn't often get to see.

Carney: No.

On this side of the table are some of the oldest pieces of artwork in our collection.

Masters: Oh, wow.

Carney: So, we have from the "Alice Comedies," we're talking 1924, 1925.

Masters: So, it's Walt Disney's first years in L.A. Carney: Yes.

Masters: Wow.

Carney: These drawings are from that period of time, but it almost looks like they've been drawn yesterday.

Masters: I mean, it really does.

You've taken good care of them.

They're well-preserved.

Carney: And these are animation drawings from the very first publicly released "Oswald."

And some of these films, we don't even have the films.

Masters: You just have these original animator's drawings.

Carney: We just have the drawings.

Masters: Wow... Carney: You know, talking about things that are lost, we're always on the search for trying to find some of these films, both the "Oswald" films and all the "Alice" films because, you know, it helps us broaden our understanding of what everybody was working on at the time and what they resulted in.

Masters: It's amazing to think that there are films that are-- would otherwise be lost to history, if not for this library.

Carney: Exactly.

We've learned over the years that the drawings are just as important as that final film.

We have about 65 million pieces of production art material-- Masters: 65 million?

Carney: in our collection, yes.

Think about it.

Masters: Wow!

Carney: Concept art, story sketches, animation drawings, layout drawings, background paintings.

Anything that went into the shorts and the features that Walt Disney Animation Studios made from the 1920s to current day is what we take care of.

And every one of those pieces of artwork has a value.

Masters: We're going to the origins of feature animation.

Carney: Yes, right.

We're going back to our first feature.

So if we wanted to see artwork from "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs," we just have to open up the cabinets, and here we are.

And to give you an idea of how much art we have... Masters: Yeah.

Carney: We begin with the first box of animation.

You just stay there.

Masters: OK!

Carney: And we continue all the way along here for animation drawings, animation drawings, all the way here.

Clean-up animation drawings, oversized animation drawings.

Then we get into some exposure sheets, layout drawings, story sketches, background paintings, concept art, all the way to right here.

And that's not all, because we have entire shelves of binders of story sketches just behind you of "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs."

Masters: That's really what makes this library so remarkable.

Carney: Exactly.

Masters: Right?

And there are a lot of animation outfits in the city-- Carney: Yes.

Masters: but most of them don't have libraries like this.

Carney: Right.

And Walt had to think of this way ahead of time.

Masters, voice-over: One thing Walt never saw coming was his own artists going on strike.

But with the Great Depression squeezing the film industry, animation workers pushed back against long hours and low pay.

Animator, historian, and former Animation Guild president Tom Sito shared how Disney's greatest triumph also planted the seeds for his toughest battle.

Masters: It must have been a big moment for any animator, whether they worked for Disney or not.

Sito: Oh, yeah, yeah.

It absolutely was, yeah, because nobody had done a feature-length film, you know, an entire movie.

Cartoons up to that point had all been comedies and stuff.

And the whole problem with "Snow White" was they said, "We know how to make people laugh, but can we make people cry?"

So when the film hit, not only did it hit well, it was like the box office champion of 1938.

It earned like 4 times more than any other movie of that year.

And it was an unbelievable success.

Masters: Not just for an animated film, but just for a film, period.

Sito: Period.

Masters: Yeah.

Masters, voice-over: "Snow White's" unbelievable success filled Disney's coffers and also stoked resentment within his studio.

Many artists and animators gave long days and nights to the film, assured they'd share in the profits.

And when Disney reneged on his promises, his employees looked to organized labor for redress.

Sito: A lot of times, people tend to think of animation in a bubble, you know?

But, I mean, we were all the Hollywood community.

The union organizing movement in Hollywood really kind of began around 1935 with the passing of the Wagner Act, which said that all American workers have the right to organize and belong to a union.

Masters: And you can't fire somebody just for trying to start a union.

Sito: Exactly.

Masters: Right.

Sito: Union organizing in Hollywood began around 1933.

Really, it all came to a head about early 1941.

Masters: And I can imagine that for these union organizers, Disney was the big get, right?

It was the biggest outfit in town.

Sito: Oh, yeah.

If you put all the studios, all the animation units in Hollywood together, it still wouldn't be Disney's.

The company had gone from just a handful of people to, like, 1,600 employees, and people are clocking in and out.

It's a factory.

Leon Schlesinger actually tried to shut out the workers.

You know, there's a thing called a "Looney Tunes" lockout.

Masters: Ah!

Sito: It only lasted for about 6 days.

Leon finally gave in.

And as he signed the contract, you know, he looked up and smiled and said, "Now, what about Disney?"

Ha ha ha!

Masters: So, who were some of the principal leaders of the Disney strike?

Sito: One of the principals was a fellow named Arthur Babbitt.

He's basically the artist singularly responsible for the creation of Goofy.

I mean, he was making very good money.

But in the meantime, like, you know, his assistant, Bill Hurtz, was being paid really low and stuff.

Bill had a wife and two kids and everything, and he was struggling, you know, to make ends meet.

They got a fellow named Herbert Sorrell.

And Sorrell was from the Set Dressers Union.

He was an ex-boxer and he was used to confrontation.

So when he would sit down with Walt Disney or something, he'd go right in his face and go, you know, "You recognize our union, or we'll shut you down!"

You know?

And Disney wasn't used to being spoken like that.

Masters: But that was his job, was to be the hated guy.

Yeah.

Sito: Yeah.

Yeah.

I knew a lot of the artists when they were in their 80s, and they're still mad at each other, based on their decision.

Masters, voice-over: The strike pushed many artists to branch out, ushering in fresh styles and new ways of telling stories that broke away from the Disney mold, but the fundamental building blocks of animation remain the same to this day.

I went to one of the animation industry's favorite haunts, the Tam O'Shanter, and sat down with voice actor Bill Farmer.

Farmer: I started in 1987 doing Goofy's voice.

In the beginning, I was just doing a copy of Pinto Colvig, the original voice of Goofy.

So, I got a cassette of old cartoons from the 1930s.

And I would just, you know, listen to that over and over.

[As Goofy] "Gawrsh, Mickey, let's go!"

And out of about a thousand people that tried out, I was the one that they picked.

Masters: Would you say that Goofy's become a little more like you over the years?

Farmer: Oh, yes.

We've melded into one.

I blame Goofy for stupid things that I do.

[Laughter] Masters, voice-over: Animator Jane Baer... Masters: You eventually left to hang your own shingle.

Baer: So, we started with some commercials and then we did some "Mickey's Christmas Carols."

When we got a little bigger, we started to bring in staff, and I just carried on until computers got more involved and I got less interested.

Masters, voice-over: And composer John Debney.

Debney: My dad lived right near Hyperion, and during the Depression, he sold papers.

And every day, this car would drive up, and it was Walt Disney.

Every day, my dad would ask Walt for a job.

So, a year goes by.

My dad asked for a job.

Walt said, "You know, kid, we're moving to this bigger joint.

It's over on Hyperion."

And he became the clapper boy.

Spent 42 years there.

Masters: Jane, let's turn to you.

So, you started with Disney, 1955.

And your first picture, the "Sleeping Beauty"?

Baer: Yes.

Masters: Wow.

Baer: Yeah.

I'd been going to art school, working my way through, which you could do in those days, but I ran out of money and Disney was hiring for "Sleeping Beauty" right at that time.

So put together my little meager portfolio and got hired.

Masters: With any feature film or television series, there is a lot of invisible labor that goes into it, and you all kind of represent different facets of the creative process that-- that goes into it.

Farmer: Yeah, I've always thought it was kind of like a jigsaw puzzle, and we each bring our own little parts, and we don't know what it's gonna look like till it's all put together.

And then you go, "Oh!

That was their vision!

OK." [Laughter] Masters: Floyd Norman, the Disney legend drew a couple of characters.

This is actually me, so... OK. Ha ha ha!

I mean, where do you go from here?

Baer: You can have something set in your mind how the character should look from the script, just reading the script.

Then you get the voice, and your whole ideas on how this character should act and look can change radically.

Farmer: Let's take this one here.

He's got a beard, he's got glasses, so maybe he's very studious.

Maybe he's a professor of something.

Or he could be very dour and kind of, uh, not humorous at all.

Debney: This guy, I don't know if you guys feel the same way, but he--these are like ♪ Din din din din ♪ Farmer: Yeah, bouncy, bouncy.

Debney: I'm so happy all day.

Farmer: Maybe he has kind of a bounce in his voice, like that kind of a thing.

Debney: And I would--I would then play something under that that was very kind of perky and-- Baer: Uh-huh.

Debney: ♪ Da duh da duh ♪ Happy.

Happy guy.

Baer: Yeah.

[Poof!]

[Curious music playing] Masters, animated: Ooh!

[Questioning notes playing] [Coughs] [Perky music playing] Masters, animated: Well, Buddy, ready to explore?

Farmer, animated: Absolutely.

Where are we off to?

Masters, animated: To finish the story.

While you were being sketched, inked, and colored, then given a voice, and music, I was learning how Southern California had a huge influence on animation.

Farmer, animated: Animation?

Like me?

Masters, animated: Like you and this version of me.

Farmer, animated: Well, didn't it all start with a rodent?

Johnson: Oh, there was so much long before the mouse.

Masters, animated: That's what some say, but it was a bunch of people, ideas, and creativity all coming together at the same place at the right time.

Farmer, animated: So, where's our last stop?

Masters, animated: Back to the Disney Studios in Burbank to meet with Don Hahn.

He's a Disney Legend.

Farmer, animated: A Legend?

Is he, like, a genie or something?

Masters, animated: No, no, no.

That was Robin Williams.

Farmer, animated: Robin?

Like a bird?

Masters, animated: Never mind that.

Let's go.

We don't want to be late.

Hahn: Oh, my God, it's so great to see it up there.

The animation's terrific, and it's fun.

And it's weird because as long as I've done this, it's still a magic trick when it comes to life.

Masters, voice-over: Back at the Disney Studios, I met with producer Don Hahn, known for Disney classics like "Beauty and the Beast" and "The Lion King," in the screening room where Walt saw the magic come to life.

Masters: This is where a lot of the magic happened.

Hahn: It really is.

This is Walt Disney's screening room.

Masters: Yeah.

Hahn: I can just stop right there.

You know, like, what else do you have to say?

But it is.

His office is through that wall.

He would have sat here-- cigarettes at the time, yeah-- full of sweating animators and staff members hanging on every word.

An assistant in the corner, taking notes, recording it all.

Masters: So, how did L.A. sort of carve out its own path?

Hahn: Los Angeles, especially in the twenties, was a place where everybody came because it was the number-one supplier of oil in the United States.

Masters: You know, everybody forgets that.

Hahn: Everybody forgets that.

It was the home of optimism and sunshine.

People were returning, at that time, from World War I, later World War II.

And it was this boomtown, the birth of modernism.

It was that place where you could come and anything could happen.

Masters: In L.A., animation became much more cinematic and then just longer- form storytelling.

Hahn: Yeah, it was about personality.

You know, at first at Disney and then at other studios and trying to develop personality animation.

And a lot of techniques were formed, like storyboarding.

We have to kind of create some sort of emotion and some sort of relationship to characters-- living, breathing characters.

What's great is, each studio has its own style, not just today, but going back to that era.

So, Walt was one of the first and deserves a lot of the credit, but he was a magnet that drew people out here from Kansas City, from Chicago, from New York, and they either loved Walt Disney and stayed their whole career or had a falling out and went to different places, which is natural.

Masters: Mm-hmm.

Hahn: It's the arts.

The other thing that happened, and this happened in the nineties, too, all the studio heads that were used to making live-action movies, are going "Wait a minute.

'Snow White' is the biggest movie of all time.

We can do that, too!"

Masters: How do you think animation changed Los Angeles?

Hahn: Animation was in its own corner of the universe, so the art of animation has moved in to be a tool in the toolkit of any filmmaker.

Masters: Mm-hmm.

Hahn: And I think that's one way it's revolutionized the world in terms of its contribution.

And that goes back to Pixar, which goes back to Lucasfilm, which goes back to Disney.

You know, so if you trace the lineage and the family tree all the way back, I think the spirit of what happened in Los Angeles, which started with that spirit of optimism and sunshine and invention turned into the ability of animation to start here, but also thrive here and now become a part of every filmmaker.

Animation is not a genre.

It's a technique.

So, sometimes they're picking up a camera, sometimes they're picking up a puppet.

And I think that's what's beautiful about where animation has ended up now, is that anybody, even us, can make an animated film with the tools that are available to us.

And how great is that?

Masters: Mmm.

This is the old animation building.

Hahn: Yeah, yeah.

It's from, well, the profits of "Snow White."

"Snow White" was hugely successful, so they designed and built this building in Burbank-- Masters: With that money, Hahn: with that money.

And so this was built in wings.

And some people say it was built as a hospital.

It wasn't.

It was built in wings so that everybody had northern light, so that all these individual wings could let the natural light in, no matter who you were or where you were.

The executives and Walt and everyone were on the top floor, then the directors and layout people, then the animators, and then it went to the basement where it went over to Ink & Paint and got painted and out the door in the Camera Department.

So it was like a factory, almost.

Masters: So, this is underground Disney history?

Hahn: Well, it's, you know, it's like a creative campus.

There's multiple buildings.

And what people don't know is, those buildings are connected by a tunnel.

Masters: Oh!

[Poof!]

[Crunching] Hahn: It was made for a bunch of reasons.

I mean, it's utilities, but also in rain and weather, artwork, which is precious commodity, could pass through these tunnels and out of the weather.

Masters: That makes sense.

Hahn: Years ago, like, you'd wander in and there'd be like, "Oh, there's a puppet from 'Pinocchio' in here," you know?

So it has a, you know, wonderful history and, you know, scary things once in a while.

It's a great secret.

Nobody ever comes down here because we're all afraid of it.

But you are very brave to come down here and see it.

Masters: Oh, I've been through lots of tunnels.

Hahn: I have heard, I have heard.

I can't wait to see that episode.

Masters: It's the hallmark of "Lost L.A." Hahn: Ha ha!

Announcer: This program was made possible in part by a grant from Anne Ray Foundation, a Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropy, and the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs.

Video has Closed Captions

Uncover Disney’s LA roots and how the city became the birthplace of modern animation. (30s)

A Hollywood Dream Job Made Real

Video has Closed Captions

Animotor Floyd Norman always knew that he wanted to work at Walt Disney's Hollywood Studio. (4m 10s)

Inside the Animation Research Library

Video has Closed Captions

Nathan goes frame by frame through the Walt Disney Animation Research Library. (2m 58s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipLost LA is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal