Arriving: Leo Twiggs and His Art

Special | 56m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Dr. Leo Twiggs is an artist and educator in South Carolina.

Dr. Leo Twiggs is an artist and educator in South Carolina.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

SCETV Specials is a local public television program presented by SCETV

Support for this program is provided by The ETV Endowment of South Carolina.

Arriving: Leo Twiggs and His Art

Special | 56m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Dr. Leo Twiggs is an artist and educator in South Carolina.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch SCETV Specials

SCETV Specials is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

More from This Collection

Find content produced by SCETV.

Weathering The Flood: South Carolina 10 Years Later

Video has Closed Captions

Revisit the "thousand-year" flood of October 2015. (26m 46s)

Video has Closed Captions

Front Porch Carolinas takes viewers to important Civil Rights locations in the state. (27m 2s)

SC On Display: The Murals of Rock Hill

Video has Closed Captions

"'The Murals of Rock Hill'' spotlights this vibrant art community. (26m 46s)

Graceball: The Story of Bobby Richardson

Video has Closed Captions

At nineteen years-old, Bobby Richardson, became the starting second baseman for the Yankees. (54m 51s)

Video has Closed Captions

The Cleveland School fire of 1923 influenced building and fire codes nationwide. (56m 46s)

Video has Closed Captions

Explore the relationship between Reconstruction and African American Life. (56m 46s)

Video has Closed Captions

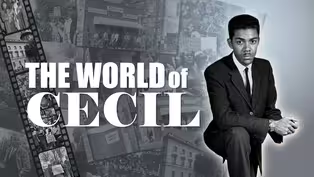

Part two continues the examination of the life of Cecil Williams. (56m 46s)

Video has Closed Captions

Explore the life of acclaimed civil rights photographer, Cecil J. Williams. (57m)

A Conversation With Will Willimon

Video has Closed Captions

William Willimon is an American theologian and bishop in the United Methodist Church. (27m 46s)

Carolina Country with Patrick Davis & Friends

Video has Closed Captions

Carolina Country with Patrick Davis & Friends. (58m 39s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ Dr. Leo Twiggs> Art is a journey and it's an adventure, and you don't really know where you're going.

There's no navigation and there's no phone to tell you how to get there.

There's no Google Play.

You have to find your way.

And when you find your way, what you do is you arrive at places that's a new adventure, so you can't go there.

You have to arrive there.

And when you arrive there, you enjoy the adventure of getting there.

And you can look back and see how far you've come.

And the joy of arrival is so important.

♪ ♪ ♪ (telephone dialing) Polly Sheppard on phone> Please answer.

Dispatch> 911 What's the address of the emergency?

Polly Sheppard> Please, Emanuel Church.

There's plenty of people shot down here.

Please send somebody right away.

Dispatch> Emanuel Church?

Polly Sheppard> Emanuel AME 1-10.... Narrator> On June 17th, 2015, a mass shooting in Charleston shook the nation.

Polly> Please come right away.

>> At first, I couldn't place it because I just didn't realize that, that was a church that I had been to early on, and it was a historic church.

Slowly the story came out, and that the people were killed and that it was at a Bible study.

I went to Bible study every Wednesday, and it was outrageous to think that somebody could go into a Bible study to kill people.

And that was so atrocious to me.

♪ Do you know that 40% of the slaves that came into this country came through Charleston?

Charleston is a very significant port for African-Americans.

They brought them in to Sullivan's Island, is where they housed them to process them.

And they brought them to Charleston, to the old slave market, and they were sold off.

So Charleston has a point where almost 80% or 90% of the African-Americans in this country can make some reference.

Of all the places he could pick, Charleston was a place to pick, to make a statement because he wanted to make a statement.

He wanted to start a war.

I think, ironically, the first Civil War started in Charleston.

So he was going to start another civil war from there.

(soft music) The church is an icon, an old icon.

It's a place where African-Americans gather.

It's the only place where African Americans for a long time could be themselves.

All of the music that came out of it, came out of the church.

This church is a particular church that is very important to the African American community.

It's not called Mother Emanuel for nothing.

It's really like the mother of our hopes and aspirations.

What he wanted to do is target the core of the African-American.

He knew that African-Americans needed the church.

And if you're going to destroy anything, you're going to destroy something that's important.

And so I knew that I needed to say something about it.

Narrator> As an artist, Twiggs speaks through his paintings.

This time, nine paintings Dr. Leo> And nine is what struck a bell with me, because there were nine victims >> In the first canvas in the series, Leo has depicted a reliquary, a place where remains, mementos associated with the death of loved ones are stored and often tucked away.

>> He aimed to create a resolution within the series of this horror.

So you have the targeting of the church.

So yes, the symbols are the target, >> The Confederate flag, which Leo has dealt with since its early days.

That Confederate flag was splashed on the church.

It was bold.

>> There was nothing shy.

There was nothing, you know, quiet about those pieces.

You felt the anguish, the pain.

And he wanted you to.

He wanted you to recognize the murder.

Sandra> But as the series progressed, the flag morphed.

And the red, which was so bloody, faded.

Dr. Frank> And then eventually, the resolution is through the ascending souls of the murdered, who are, in a sense, martyred.

Dr. Leo> And then when I got to the last one, I had to think, how do I end this?

What happens when slaves come over and they're in the holes of a ship, and they come up above and they see a new world for the first time.

And what was east is west and what was south is north.

And they are completely disoriented.

And then they move into slavery for the rest of their lives.

What was that like?

And then I thought something that James Weldon Johnson wrote and what was called the Black National Anthem.

And it says, we have come over a way that with tears has been watered.

We have come treading a path through the blood of the slaughtered.

To me, the terms we have come was a story of our journey that there will be things that happened, like Mother Emanuel, afterward.

And you have seen that it has.

And there were things that happened, like Mother Emanuel before.

And so it was a story of the struggle.

(music ends) Sandra> The Requiem for Mother Emanuel was first shown at the City Gallery in Charleston on the first anniversary of the shooting.

Narrator> The exhibition toured prominent museums and galleries in multiple southern states.

♪ Dr. Marilyn> The reaction to that exhibition was incredibly positive.

Lynne> Over the course, the Requiem exhibitions stay here in Spartanburg.

We had over 2000 visitors.

Then we had the opportunity to invite the Carolina Panthers football team, Ron Rivera> From Cam Newton to Charles Johnson and Ryan Kalil and Luke and Greg Olsen and Thomas Davis.

Those six young men got an opportunity to sit there and listen.

Guide> And it is a transition from a tragedy, a moment of terror, working your way up to a moment of salvation and forgiveness.

Lynne> The Panthers, brought a whole new audience.

We had people from every walks of life.

Sandra> The reaction of people.

I can hardly talk about it.

And this is an example too, where Leo's art brought people together.

At those openings, there were Black Americans.

There were White Americans.

There was no difference.

There was mourning and there was sadness, and there was coming together.

Dr. Leo> And that's the first time in the history of my painting that people went in and looked at the works and came out crying.

>> I don't weep easily.

I'm afraid I'm a little bit too cynical.

But when I first saw the exhibition of the Mother Emanuel works, I wept.

And that is because my relationship with Leo Twiggs was such that realizing what it meant to him, it also meant to me.

>> We've lost the ability to lament as a nation, as a culture.

And I think in Leo's case, a lot of his paintings are those objects of lament, these icons that call us to weep, that call us to be honest about the pain, to be honest about the horror, but then to know that we have camaraderie and kinship in this suffering, then to offer a way forward.

Sandra> At the end of the series, there was such hope.

The X marks the cross where the bodies were.

They morphed into crosses going up to heaven.

Luke> In the final painting of the Mother Emanuel series, you see, the profile of the church has been abstractly turned into a path.

Lynne> He connects it back to our history and to acknowledge that this stony road as being trod for 400 years, and that we are far from winning the race, unfortunately.

But he ends with a note of hope, because he believes that we can find common ground, that we can find ways to, as he says, crossover or move beyond to a better understanding of one another.

♪ Sandra> I think that Leo will be most remembered for the Requiem series.

William> Even the tragedy of Mother Emanuel that passes from the public eye or public mind, but Leo's work will not.

♪ (traffic sounds) Narrator> Leo Twiggs was born in St. Stephen, a small town in South Carolina, 50 miles north of Charleston.

His childhood family house still stands as a monument to his past.

(birds tweet) Dr. Leo> You know, this is where it all began for me.

Because this is home.

And this is where it started.

And I still get chills because I remember so much of what happened here.

And the old house behind me is where I grew up with five brothers and a sister, the seven of us living in the house.

Narrator> Leo's father, hailing from Mississippi, traveled by riverboat on the Mississippi and throughout the south, eventually settling in St. Stephen.

Dr. Leo> So my dad had a lot more experience of the other side of the world.

My mom never left here.

She lived in the town that they met and they got married.

And my dad built this house, probably built in 1936.

Home place.

I know this.

That's the coffee table that was in the house when I grew up.

Yeah.

And we had a...that was for, In fact, that chimney served four rooms: this room, that room and the phone in here.

And what was unique is my dad got these French doors between dining room and this is the living room here.

That's the dining room table there.

But one of the unique speaks of the house are the double windows.

These are double windows.

Nobody really had that kind of double windows on both sides.

(soft piano music) I used to look through that window and see a bird flying by, and I'd say, I wonder where that bird is going.

I wonder how that bird sees...us down below.

And so my imagination was always looking at where things were and what was going on about me.

♪ That, and a lot of that has shown up in my paintings.

Things that I remember.

We used to have a sofa over there that went a long time ago.

But, some of the shapes end up in my paintings, like...this.

♪ And one of the things that I had started doing is painting pictures of the people who came by this house with me.

A lot of my earlier paintings were about growing up in this place, and what I remembered.

You noticed the front porch.

I spent a lot of time on it because when I was growing up, I read a lot.

I read books that I could get my hand on.

♪ Narrator> At 13, Leo began working as a janitor at St. Stephen's movie theater, where he learned to operate the projectors.

Dr. Leo> And when I got the job at the theater, I didn't spend as much time in the house because I was always gone.

My father was ill, and he was ill for quite a long time.

The night he died was the night that I ran the motion pictures' projectors solo for the first time.

And I remember my brother came up there and said, you know, daddy died.

And I couldn't go because I was operating the projectors I couldn't go.

I was about 15.

And that's when I got the job in the theater as a projectionist.

Narrator> As the eldest child, Leo became the man of the house overnight.

This is where I worked those early years.

That's where the booth was.

And I could work because nobody would know you at the theater, you know, we're in the booth above the segregated balcony.

So nobody knew who was running the projectors up there.

I would come back at night from the theater.

I usually got in about 1130.

I had to walk, and it's exactly a mile.

I had to come through that dark area.

And my mom always thought about what could happen to me and all of that.

And there was a dining room over there.

My mom would always have the light on in that window, and I would look across the field and see the light.

And I knew I was home.

(music fades) But sometimes I'd see this figure approaching me, and it was dark.

There was no light on the road.

And you could walk in like John Wayne or something... and he'd say, hey.

And I could recognize his voice.

And that was my Uncle Silas.

And he was going downtown toward town.

Nothing was open.

You know, I wondered, where was he going?

But what happened is he walked down the road, and then he turned around and walked behind me, just far enough back so I would not notice him.

And when I found that out, it gave me the courage that somewhere he was around.

He shows up a lot in my painting.

A lot of the men in my paintings with the hat pulled down reminds me of my Uncle Silas.

(music fades) I have a painting called The Birth of Blues, and I always felt that African American mothers were never satisfied if their sons or their daughters were out, especially their sons.

And I believe all over the South there were mothers like my mom waiting for their sons to come home.

And some of them didn't Emmett Till didn't get home.

And I always thought that that's where the blues came from.

That's what Black singers sung about.

So that shows you how just an incident evolved into my painting.

♪ ♪ ♪ I call that painting, Dreamers.

As I painted all those years.

I had to return to the house.

And I put things in it that are metaphors that I've used over my career: the Confederate flag, the targets.

And in the house what I did was, simply did a window and I have two boys looking out.

You know, this is the kind of dilapidated place where they live, but there are other places that they can go.

They are dreaming about other places.

That painting is kind of a synopsis of my life.

♪ If you don't know where you came from, you won't know where you're going?

And so this house has become a kind of symbol of our lives, of where we came from, of how we came to be, of all the things that happened to us, that made that evolved.

♪ When I graduated from high school, I graduated top of my class.

But we were poor.

College was not even on the radar because nobody went.

So you didn't even think about going.

And a minister, a White minister, in my hometown came by and said, I want to take you to Claflin College.

♪ Narrator> The minister took Twiggs to meet the college president, leading to his enrollment at Claflin.

His mother sold two cows to fund his first year's tuition.

A year later, he became the projectionist at the Orangeburg's Carolina movie theater.

Dr. Leo> So I made enough money not only to pay my tuition, but also to send money home to help my mama.

This is the route I took from the theater every night.

It was shorter than going Main Street, and so I turned here and walked all the way down this road to the end of the street.

And that's where I turned to go home.

And... this is the church where I had to walk by each night, but it was important to me, because this is where the pastor who took me to Claflin.

That changed my life forever.

♪ Narrator> Another man that changed Twiggs' life is Arthur Rose.

Dr. Frank> Arthur Rose was Dr. Twiggs' teacher at Claflin, and he was a witty, inventive, very impressive person.

He was a sculpture and welder, but he was also a painter, and he would work in very unusual materials, very cutting edge.

There was this very innovative atmosphere in Orangeburg that was surprising and that was also very stimulating.

Dr. Leo> And he took me under his wings, like a father.

Took me on a trip to Florida, the National Conference of Artists.

I was the only student there.

I met many of the famous artists that we know as a student.

Dr. Frank> These people were luminaries nationally and internationally in the art world and in the African-American art world as well.

Dr. Leo> And he was fiercely political.

He was always marching in the streets, but he was a person who taught me about art.

♪ After I graduated from Claflin, I could not attend a higher education university in South Carolina because they were segregated.

Sandra> He was a determined young man, saying not being able to go anywhere else in South Carolina for further education, so he goes to New York City, which was the hotbed of art in those days.

So what was a curse ended up being a blessing for Leo.

♪ Dr. Leo> When I went to NYU, I met Hale Woodruff.

Narrator> Hale Woodruff was an iconic African American artist celebrated for his significant contribution to the Harlem Renaissance, focusing on themes of Black history and civil rights.

Dr. Marilyn> So he would've been an enormously powerful artist for Dr. Twiggs to have learned from, to have come up against, not only as a really strong artist, but also as a Black man.

Dr. Leo> So I was in his class and I started painting, and they were doing abstract expressionist, from at the time, they were slinging paint all over the place and they were doing this Jackson Pollock kind of stuff.

I was lost, because I was used to doing tight things, and they were just slinging this paint.

And so I had a course, called field trip to museums.

And every day I would walk down one of the avenues, Third Avenue, Fifth Avenue, And I'd look at the galleries and I'd look at art.

And I'd go to the Guggenheim and I'd go to all the museums and I just fought through it.

He never said a word to me.

And at the end of that class, we all had to have a critique with all the things around.

And one guy said, I think Twiggs is the most improved person in this class.

I would have said, I know he could do that.

And yet when I was there, he never said a word to me.

He simply let me fight it through.

Dr. Marilyn> One of the things about good teachers, is that they don't make you follow their form.

They allow you to find your own way.

Dr. Leo> And to this day, I remember things he said, like, for instance, that we African Americans must find symbols in our culture, to make statements about life.

I thought about that, and over the years I have used that cow, which is, I think, a docile creature.

I have used chickens, you know, hands who are dominant.

Dr. Marilyn> That was brilliant on Hale Woodruff's part, but it was also essential that Leo listened.

He stepped up to the plate and did paint about his life and the experiences he knew.

Narrator> In 1967, Twiggs enrolled at the University of Georgia.

Three years later, he made history as the first African American to earn a Doctorate in Art Education.

Dr. Leo> First day at the University of Georgia, I'll never forget, Lamar Dodd, who was head of the art department when I came in, and he spoke to me, showed me his work.

And in the end he said, Leo, we don't think of you as a student, we think of you as a colleague.

And that to me, was a great introduction to my doctoral program.

(soft jazz) Narrator> Twiggs first encountered batik, while studying briefly at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Upon returning to South Carolina, he introduced this technique to the high school students he taught.

Dr. Leo> And them kids would do all kinds of stuff, you know, they'd dip it before it was completely dry, and they's put wax on it, and they got stuff that I didn't even know you could get with it because they broke all the rules, you know.

And I was fascinated by the colors they got.

And I began to say it to myself, what happens if I try to paint with this?

I spent the first five, six years, or even ten years learning the medium because there's nothing to look at.

I invented this way of painting.

Luke> The famous saying, you know, artists borrow, but great artist steal.

Leo hasn't been able to steal a lot when it comes to his actual technique, he's had to pioneer it.

Dr. William> I was fascinated by the fact that Leo Twiggs had taken a medium that's considered craft often, and turned it in to a vehicle for fine art.

Dr. Marilyn> Up until very recently, the division between what is fine art and what is craft, has been an incredibly huge wall between the two.

Dr. Frank> In the hierarchy of arts established in the West, painting is often seen as the thing that's at the top.

So if you have someone like Dr. Twiggs who is painting with dye, some museums might see this act of staining as opposed to painting as craft, and for that reason might still reject the sort of postmodern quality of what he's doing.

Luke> We presented Leo's work to a major national museum, and the director there, looked at the pictures and said they lacked depth.

Now, if there's any one thing that Leo's paintings don't lack, it's depth.

That dye creates an unbelievable depth of color.

Dr. Leo> What's fascinated me about dying is that dye, penetrate the fabric, whereas paint lay on the surface of the fabric.

And even from my earliest time of painting, it just seems to me like painting on top of a surface, did not really do what I wanted it to do.

Batik, the dye, forces you to look into the fabric rather than on the surface of the fabric.

That is the way I have to do it, because it captures my feeling of down home.

It captures this stuff, you know.

I think growing up, we had old things, you'll see a lot of that here, and the paint is peeling off and all of that.

It was dingy, but there was something kind of elegant about the dinginess.

Lynne> I think certainly Leo, because of his vast education, obviously knew what the prejudice against batik may have been.

But Leo has constantly faced up to prejudice, and used it for a greater good.

♪ Dr. Frank> Batik as a method is outrageously laborious.

Sandra> I think the process itself, is who Leo is.

He's very thoughtful.

He's very contemplative.

Luke> Batik is painted backwards.

Wherever you're seeing the whites, that's where he saved it with wax.

Wherever you're seeing the deep colors, those were painted last, layer upon layer of saving different colors with wax.

He never sees the painting, until his wife, Rosa, irons off the wax at the end.

And I've talked to him, and he said that he can hold between 20 and 30 layers of color in his mind and know every single detail of that painting.

Dr. Frank> So these works have this wonderful quality of spontaneity, but they're just not spontaneous at all.

And that, in a way, characterizes a great deal of what he does.

It's very carefully thought out, very controlled.

Dr. Leo> Dye is unforgiving, I mean, when you put it down, it's in the fabric and you can't erase it.

So you have to know what you're doing from the get go.

And knowing what you're doing has to do with orchestrating your feelings, orchestrating your applications, orchestrating your ideas, and then coming up with something at the end.

(mellow jazz) I like the, the cotton because I grew up here.

I grew up where cotton has grown.

Cotton holds the dye.

The dye seeps into it, and stays a long time.

So you get deeper colors.

Dr. Marilyn> Sometimes he would use cotton calico that had the print of the material, Dr. Leo> But I also use pattern fabric.

I have to just be very careful that the pattern doesn't overpower the image.

Dr. Marilyn> Guess I thought, well, that's, you know, that's a reference back to his home and to his mother and to all of those kinds of things.

But for him to allow that pattern of all of those other references to become part of his expression, that's pretty damn pushy.

Luke> One of my favorite paintings is Mother Emanuel Remembered Nine .

This painting is one of the best ways to really understand the interaction of symbols within Leo's work.

The painting itself, is painted on cotton.

Cotton was the main product of the South, during slavery.

So he's using a product to paint on South itself, but also recognizing the history of the enslaved peoples that worked the cotton fields and then turning it into a piece of art.

But beyond that, this is a very specific kind of cotton fabric.

It has almost an antebellum pattern with flowers, that you can see popping through.

And the ironic thing is, that when you put a Confederate flag with its bright reds and these intense pigments, the flowers show through better.

They fade white on white, but when you add that dye, all of a sudden there's this huge burst of these flowers.

That's Leo's sense of irony about the South.

It's both bloody and violent and horrible, and yet the South is famous for its hospitality, its gentility, its sense of values.

And how can those two things coincide, like a paradox?

It can be hard to discuss it in a narrative, but you can symbolically show it very quickly.

It's very moving.

People have often been brought to tears by Leo's work, even if they don't understand all of the various levels of symbology and how it's all overlapping on each other.

They can feel what he means.

They can feel the spirit of the work.

(music fades) >> Into the '70s, probably one of the most important series of works that he did, was Commemoration , where he was working on the appropriation of the Confederate flag.

Dr. Frank> So when he was working on his dissertation, going back and forth to Georgia, he would go through lots of rural communities because he had to commute from Orangeburg.

Dr. Leo> That's how I got the idea for the Confederate flag, driving the back roads, going to Athens, Georgia.

There are a lot of colonial homes, a lot of antebellum plantations.

And on Confederate Day, they would have these flags hanging out, and it was like going back in time.

It was surreal, and I was fascinated by that.

Dr. Frank> He understood in a way that this was an assertion by a people, who may sometimes have felt defeated by the aftermath of having lost this great gamble of the Civil War.

Dr. William> That flag symbolizes what happened in the Civil War, and continued to symbolize, even today, for some people, the attempt to maintain a White culture, to deny the validity of Black culture, to deny the validity of Black people in some ways.

Dr. Leo> For African Americans, a Confederate flag says only one thing, it's White supremacy.

It's you have to stay in your place, and that's what it says.

You know, one of the things that I'm always, reminded about my state is that this is the place where the Civil War began.

And for all those people who say it was about history, that was not true, because I read the articles of secession, and it was about slavery.

(slow bluegrass music) I've always painted Confederate flags, but not the kind, you fly around on these pickup trucks.

My Confederate flag is a deteriorated old image, As if, if your ancestor was in the war, and he had an old flag in the trunk, folded up, moldy, even shot through with bullet holes, and you pulled it out, how would that flag look?

That is what heritage is all about.

When you fly a polyester flag above a statehouse, that is not heritage, that's exploitation of an idea.

Luke> The images evolved in the early works, it might be a faded blue or even a white image, like a memory.

Sandra> The flag is a tattered flag.

It's a flag that's been put in a chest for many years.

>> You can't look at one of his Confederate flags and say that it was made without empathy.

He's thought long and hard about how that flag would look if it was sitting in an attic or in a museum.

That's what empathy is.

He's really considered the other side.

Dr. William> Leo is commenting on the flag as representative of all of those things, but he's also saying that, that is part of his heritage, as much as it is part of, say, my heritage.

Dr. Marilyn> Instead of being fearful of what that means, to come at it straight on is an amazingly brave, fearless kind of thing to do.

And he did it in his own quiet, not screaming and ranting and raving kind of way.

But he came at it straight on and made people talk about it.

Dr. William> Batik helps in that, in his emphasis on the flag as a deteriorating idea.

Dr. Leo> With batik, I could get the oldness because I could crush it, and I, and you couldn't get that with paint.

Sandra> Leo takes that symbol and takes away the power from the White supremacy and makes it his own.

Lynne> I think there is a wisdom and a wit to the way Leo is able to take a technique, and then symbols, and turn them into a tool for expression and education.

They're marvelous, all the more marvelous for that inversion.

(music fades) Dr. Leo> This is a railroad crossing that really crosses between one side of town and the other side of town.

(slow western music begins) I always felt that life was a series of crossings, that is really what happens with us.

We have to cross over things, and it's very difficult.

This whole business of the Confederacy and segregation and the way we've been treated, even though it happened to us, we have to get over that.

And so that's the way the whole idea come.

You know, as an artist, you deal in metaphors.

Art is more than just putting paint and drawing things, art is about images and ideas.

And so this crossing became a metaphor for crossing over, how we have different things in our lives that we have to cross over.

(music fades) Dr. William> We sometimes forget, in talking about Leo as an artist, that he was also an educator.

(piano music begins) Narrator> Upon graduating from NYU, Twiggs joined the faculty at South Carolina State College, now South Carolina State University.

>> Leo could have taught in numerous different universities.

What did he choose to do?

Luke> Given the history of what he's experienced, You know, South Carolina not allowing him to take degrees in their state because of his race, and yet he still returns.

Dr. Marilyn> His desire to come home was two-fold.

I think he wanted to be home, he wanted to have the proximity of family and friends, and what was incredibly important to him.

But I think he also knew that he could make a bigger difference here.

Dr. Leo> When I went to Claflin, I had an art professor named Arthur Rose, and Arthur Rose could have gone any place like I did when I started working, but he chose to stay at Claflin, and he stayed there for me.

And when I graduated from Claflin, I always said that I needed to stay and do the same thing for the other students in the state.

And we go around the horn from Texas to North Carolina, and South Carolina was the only southern state where state supported historically Black colleges did not have an art department.

Because they already established in agriculture and mechanical.

They taught bricklaying, masonry, homemaking, practical stuff.

Some people say, you know, designed to keep Blacks in their place, so to speak.

And so when I came in 1964, that was my aim to build an art department.

(piano begins) Narrator> Twiggs first established a discipline based art program and recruited dedicated professors.

♪ Dr. Frank> Before I got there, he had started to show works in the basement of the library.

So he used that as a gallery until he could create a space.

Narrator> The humble basement gallery impressed the college president M. Maceo Nance, who secured funds to build a new museum, with Twiggs leading the design collaboration with the architect team.

Dr. Leo> Because I told them that if people walk up on the campus and say, where's the museum?

And they go through the whole campus and don't find it, the building isn't worth seeing.

♪ Dr. Frank> The main thing he thought about it was to create an extraordinary exhibition space.

And so there's a 3500 square foot gallery equipped with modular walls that you could reconfigure that gallery space.

And so he was absolutely instrumental in the design.

Dr. Leo> In 1988, Ebony magazine came and did a story, a three page color spread on our museum and planetarium, because it was so unique, no other historically Black college had that.

Narrator> The mission of the museum is to collect, display, and preserve African and African American art.

With no budget, Twiggs had to be creative in acquiring donations to support this mission.

Dr. Frank> Among the early things he acquired, would be a Nancy and Roderick MacDonald Collection of African Artifacts.

He also acquired the Harlem On My Mind photographs.

These were extraordinary works.

Dr. Leo> And then after that, of course, we got a collection of African textiles, sculptures... and so that was the basis of our collection.

Narrator> In 1988, the art program was elevated to an art department, Twiggs achieved his goal.

Years later, he collaborated with African American architect Harvey Gantt to build a home for the department.

Dr. Leo> And I had each members of my department, design their space.

(It) would be like the printmaker, he knew he had to have a ventilated space, and I got their requirements, and I gave it to the architects said we want all of these things in our building.

Narrator> In 1999, a year after Twiggs retired from teaching at South Carolina State University, the brand new Fine Arts Center stood tall on campus.

(music fades) (soft guitar music begins) Narrator> Over four decades of teaching in high school and college, Twiggs mentored students to win countless awards at state and national competitions.

♪ He has kept a photo of one of his students, alongside her artwork, from 1966.

Dr. Leo> So we were doing linoleum cuts.

She drew a drawing of two students working.

I gave her a piece of linoleum, I said, you take it home and then you give it cut and you bring it back.

She brought it back and it was really very nice.

And I said, but it doesn't have a ground, put that line in there to create that ground, and that's it.

She put the line in there, printed it, it won a national award.

(music fades) Scholastic magazine wrote me and said that they wanted to use her painting as the advertisement for the next year's Scholastic Award.

And when they used it, they reversed the print because where everything that was Black, was White.

And so instead of, two Black girls at a table drawing and working, it became two White girls at a table that was drawing, and working.

And I have kept that, because to me, it's a symbol of the times.

(soft music) Narrator> During that time, the Civil Rights Movement was in full swing, facing brutal suppression.

♪ On February 8th, 1968, State Highway Patrolmen opened fire on African American students protesting racial segregations at South Carolina State College, resulting in the death of three students and injuries to 28 others.

(melancholy music) Dr. Leo> The Orangeburg massacre happened, and it was traumatic.

I was at the University of Georgia, and my family was here, and I went home on weekends to see them.

Well it turned out, I went home one weekend, I couldn't even get into the campus because they had tanks on the highways up there, and I had to give credentials.

It was a trying time, and I think after that, when I started teaching students, they were more keenly aware of their place in society, more keenly aware of what people might be thinking about them.

The campus was really not the same again, and the state has never apologized for that.

And that's still a sore spot in this state.

♪ Narrator> Twiggs was also more keenly aware of his responsibility as an artist and an art educator.

(music ends) Dr. Frank> That's one of the things Doctor Twiggs consciously and conscientiously advocated for, African-Americans to be included, advocating for more diversity.

If he's in the room, he would always do what I would call, the difficult conversations.

He would be the person who is fearlessly going to go forward and say what needed to be done.

Dr. Leo> One of the things that I've tried to do, even in my painting, is to show people where the wrongs are, is to work on the psychic of the individual, and to let them see what is happening.

(silence) (piano starts) Narrator> Following in the footsteps of his mentor, Arthur Rose, Twiggs became an artist and professor, and he looked forward to passing the baton to his students.

Dr. Leo> To me, when I look back on my career, I'm so proud of that because my students did so well and all of them are teachers.

But they still do their artwork, and what we try to do is give our students a strong background, and then after that, we tell them to get your stories from your life.

William> He wanted the same experience for his students that he had, had, which in some ways is Socratic, in that he is questioning them, asking them to bring forth from their own creative juices.

Dr. Leo> And when they do that, they are much more creative and they begin to see the environment in a different way.

And that was so important to me as well.

♪ Narrator> Twiggs is also proud to have designed the official seal for his university.

Dr. Leo> When I did the seal, one of the things I wanted to do was not do a circular seal.

So I did an oval and did a palmetto tree.

1896 and, Orangeburg.

It's always going to be a part of me and of course a part of the university.

And it's on all the diplomas.

And so it's a reminder that I did something of value while I was there.

♪ Narrator> Twiggs believes that an artist's creativity should be a part of his being, and extend well beyond mere studio work.

♪ He designed the logo for Claflin University, his alma mater.

He worked with an architect to transform a historical library into a museum named after his mentor, Arthur Rose.

♪ He designed the windows for the Claflin Chapel, incorporating elements of African Kinte cloth pattern and sculpture.

♪ In designing the Tisdale Memorial, he applied the ancient Chinese concept of yin and yang.

♪ He collaborated with architect Clarence Addison to design his own house.

Drawing inspiration from a traditional African house found at a Louisiana plantation.

♪ Twice in 2001 and 2008, Twiggs created Christmas ornaments for the White House, one of which depicts the former home of Dr. King's spiritual mentor, Benjamin E. Mays ♪ Dr. Marilyn> But there's so many other things.

I mean, there's also his being an amazingly literate poetry, music, the jazz music, Luke> In my many conversations with him, I'm constantly blown away by his breath of knowledge of so many different topics.

Dr. Frank> That he could quote contemporary rap artists.

He'd quote Run D.M.C's poetry in his class, and the students would just be blown away.

They would just be in shock.

And then he could quote Langston Hughes and he would do it seamlessly.

Lynne> He is, in that sense, a Renaissance man, that he has a commanding understanding of so many fields.

And the way those fields infuse his art just add to its depth.

(music fades) Leo holds a distinct place in the history of South Carolina art.

Sandra> He's huge in South Carolina art and in southern art, too.

I think that the state of South Carolina has made a very good show of recognizing how important he has been.

♪ Narrator> Leo Twiggs has garnered numerous prestigious awards throughout his career.

♪ He is a two time recipient of the Verner Award, the South Carolina Governor's Award for the Arts, and has been honored with the Order of Palmetto, the highest civilian award bestowed by the state.

♪ However, the recognition he holds most dear came from his wife, Rosa.

Dr. Leo> I got this award from her, I just... and that was just amazing.

I don't know how she came to do that, But this an award that she gave me.

♪ This is to my husband on our 33rd anniversary day.

Thanks for your love, patient, understanding, and for being there when I need you.

I love you so much.

When I speak, I say she has become the wind beneath my wings.

She was kind of in the shadows.

And she allowed my career to blossom.

She's participated in the process from the outset.

With batik, you have to remove the wax.

What she does is irons it out, but she has removed the wax from everything.

Lynne> I think her doing the ironing says more about the trust they have in each other.

The partnership that they have.

Luke> The two of them are a force.

I can't think of one without the other.

Dr. Leo> She was so supportive, so understanding of what I was going through as an artist.

I've had a great family and I've had a great career, and I would not have had the family part of it, nor the career part of it, if it were not for my wife.

Lynne> She and Leo have lived the history, the hard history of being African-American in South Carolina in the 20th century, and they share that experience and that commitment.

And it's an inspiring relationship.

(church organ music) Narrator> In July 2023, eight years after the Charleston Church Massacre, Virginia Theological Seminary hosted an awards ceremony honoring Leo Twiggs.

Their deliberate choice of another Charleston sanctuary, mere blocks from the Mother Emanuel Church underscored the impact of Twiggs' art.

♪ >> God speaks in many ways, and on this Sunday, as we sit in the presence of one of America's greatest artists, let us all pause and express our gratitude to those who bring the Word of God through the visual arts.

>> With deep joy and gratitude, the Virginia Theological Seminary gives you the Dean's Cross for servant leadership in the church and the world.

You have lived fully, the well formed life in Christ.

(applause) (applause) (chorus singing in background) Narrator> Virginia Theological Seminary stands at the forefront of a growing number of institutions, striving to make amends for their involvement in America's slavery.

To transform its 200 year old campus into an environment truly reflective of God's justice and inclusion, the seminary's leaders reached out to Leo Twiggs.

Rev.

Ian> And we purchased an extraordinary painting called The Death of George Floyd Dr. Leo> With the death of George Floyd, what got me was the nonchalance, the kind of empty.

You know, you putting somebody's neck on there.

You should feel something seeping out of him, his life going.

Yet, there was nothing.

Nothing.

And that's probably what happened in Germany when they were killing the Jews in the chambers, no feeling whatsoever.

No feeling, this is another human being.

Rev.

Ian> The first time I saw that extraordinary painting, the death of George Floyd, a searing pain ripped me apart.

As you watch this fast hand of White racism crushing the life out of Mr. Floyd, Dr. Leo> You could recognize the knee, and you can recognize the black figure.

There's no other human being in there.

And I did that intentionally because what I wanted to say was just like Mother Emanuel, George Floyd was an incident.

There'll be more George Floyds.

There have been.

There will be Mother Emanuel.

Just had one in Brooklyn.

So you understand the lynchings and all of these things that as horrified as you are that is just another story, that has happened to us.

Rev.

Ian> We deliberately create opportunities and occasions for people to sit and study these paintings and listen to exactly what God is saying through the work of Dr. Twiggs.

That policeman was not just one bad apple.

The narrative is the death of George Floyd was a result of a culture and environment that goes from Confederacy through segregation to Mother Emanuel Nine through the bullets on the backs of young African Americans.

And all of that is crushing the life out of this man.

Dr. Leo> And that shook America to its core, the whole world to its core.

♪ Rev.

Ian> And then we asked him to paint a batik painting for us to focus more on grace.

Dr. Leo> I thought about what to do, and especially Episcopalians, because that's the Anglican Church, the denomination of the slaveholders.

All of their churches were actually constructed by slaves.

And so what I did was I used a church in my hometown, which was an Episcopalian church.

I used to see this elegant building across the field, and I couldn't go in there.

And I remember my grandmother saying to me that her mother, was a servant, and she took care of, slave master's children in that church.

And I thought, the transition from slave owners, their religion, And now the head of that church is a Black man.

What I wanted to do was to kind of show the transition.

Rev.

Ian> So you have African-Americans in fields and church buildings.

You have the stories of young people, exploited by institutions.

You have this predominant White leadership, Dr. Leo> And finally, the domineering figure where the leader of the church, with all that regalia, Rev.

Ian> You have Michael Curry, Presiding Bishop, the first African-American to be the presiding bishop of this White church with its complex history and a slogan Curry often utters, which is, "Our values matter."

Dr. Leo> Our values matter, at which he's saying that it doesn't make any difference about the color of your skin.

It's the value of the church that really matters.

And to have that said, in a denomination that catered mostly in its beginning as the place where slave owners worshipped, it was so significant to me.

♪ Rev.

Ian> Dr. Twiggs' art is extremely effective.

It's harrowing.

It's disturbing.

It's deeply evocative.

It invites conversation, invites reflection, and invites prayer.

Rev.

Ian> When you hear these words, visually, I really do believe we need to hear the Spirit of God.

We really do need to hear the voice of God.

We need to listen to the challenge that's been captured in that art, and the invitation for the world to be different.

(choir singing) Virginia Theological Seminary has an award entitled The Dean's Cross for Servant Leadership.

The idea is that although we're a graduate school, we're also a place of formation for men and women to preach the gospel.

Authenticity is the single most important part of formation.

When you work on a human life for the goal of making sure that they are authentic persons for ministry, what we need are models, literally, persons who embody that formation in their own lives that we can celebrate and lift up and honor.

So we created this award.

We honored a president's wife, who worked hard on literacy and supported her husband.

We honored a secretary of state who was the first woman Secretary of State in the history of the United States of America.

We honored an environmental poet, Wendell Berry, and we honor Dr. Leo Twiggs.

And we honor Dr. Leo Twiggs because his art is for the nation.

His message is for the nation.

And he is a man who's lived the journey personally, having to overcome racism at every turn in his professional and personal life, and now is a prophet to our age.

He is a person telling us what we need to hear.

Let us be grateful that such artists are the very voice of God to our age and to our time.

Amen.

(piano jazz) ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

Support for PBS provided by:

SCETV Specials is a local public television program presented by SCETV

Support for this program is provided by The ETV Endowment of South Carolina.